THE LAST SURVIVOR AND OTHER MODERN JEWISH PLAYS encompass six decades of Jewish life in the United States. These works provide an opportunity to repair history — to revive the dead, dispatch sentimental stereotypes, come to grips with life’s disappointments and losses, and then finally to find the joy.

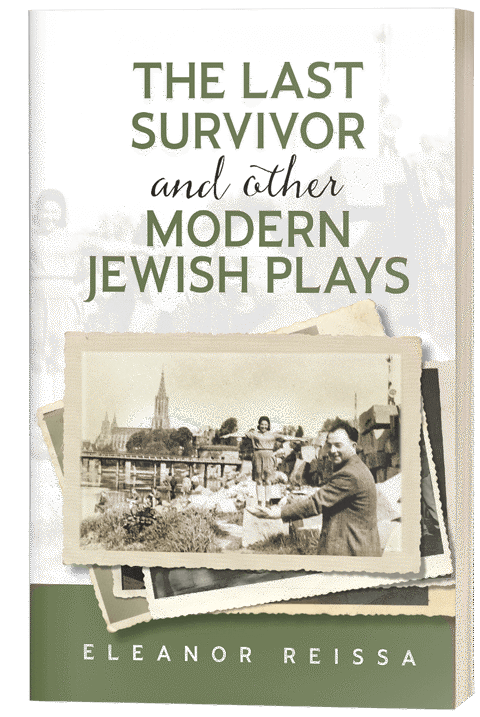

All of the plays are meant to be about the Holocaust survivors who made it out alive — and about those who did not. At one time they seemed to be everywhere but then all of a sudden, they disappeared from the face of the Earth, as though they never existed. Fragmented memories and small jagged black-and-white photos seemed to be all that was left of them.

All of these plays are bound by the genetic strands of post-Holocaust DNA: the enormous expectation of loss, plus a peculiar “entitled-yet-undeserving” syndrome not shared by those who did not travel in the wake of the death camps: How can you complain about anything after the Holocaust? How can you be entitled to want more when they had so little? How can you ever turn to a friend and say, “You know what, I’m starving.”

Their legacy is a rich one — perseverance and passion and hunger for life. These people existed.

These plays hope to contradict the claim that nothing lasts forever.